Leadership in the Punjab Pre-1947

MUHAMMAD SALEEM AHMAD

This paper does in no way concern itself with the leadership crisis in today’s Pakistan or the Punjab. What it intends to explore in a modest way is the nature and character of Muslim leadership in terms of their relationship during the first half of the twentieth century in the Punjab.

The onset of the twentieth century witnessed among the Muslims of India a phenomenon that could only be described as strange. This was the Muslim readiness to act politically at all India level. Till this time Muslim India by and large had remained inactive in this regard on account of the advice given to them by the grand old man Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898). We need not discuss here those of the details which led Muslims to act as politically as there exsits literature on the subject in plenty. What is ignored, is the fact that those who came forward to organize the Muslims on political ground belonged to the middle strata of the society-men of independent professions such as lawyers, journalists, doctors and others. There was however one exception where leadership was provided by the upper of aristocratic class. This happened in East Bengal. But this was much appreciated and welcomed. Commenting upon the situation the Mihir-o-Sudhakar, Calcutta, 14 June, 1907 observed thus:

“Since the dawn of history, it has always been found that leaders of public opinion and patriots have been drawn from the middle strata of the society. But it is a peculiar feature of the history of Muhammendan generation in East Bengal that the patriots have sprung from the aristocracy. But the position changed in due course of time, sooner than thought”.

Like everywhere else in the country Muslim leadership in the Punjab also emerged from Muslims of the middle class.

According to the 1901 Census there were about 10,825,698 Muslims in the Punjab listed as Ahle Hadis, Shiah, Ahmedis and Sunni Muslims. The latter however abounded (Census of India 1901: 14, 285). As for their literacy in languages there were 367,871 Urdu speakers, of them only 166210 were Muslims and the rest were Hindus and Sikhs. In terms of social and economic progress of Punjab Muslims it had been observed:

“Mohammedans have confined the education of the youngs to the religious doctrines (which could be had without resorting to printed material?) just as their literary activity is confined to matters of religion. Similar remarks apply to the cultivating classes (of Muslims) which are generally retrograde in every thing save numbers” (Ahmad: 29).

But this did not mean that Muslims in the Punjab did not have the upper or aristocratic class. Indeed there was a sizeable number of Muslim landed aristocracy which enjoyed a considerable influence and power in the region and doubtlessly true that it was a match the Hindu and Sikh landholders. But unlike upper class of the latter two mentioned here the Muslims aristocracy was completely obvious of their less opportune coreligionists and leaned heavily towards the government for their personal benefits. Take for instance the case of Omar Hayat Khan Tiwana (1841-1917), a leading man of landholding group of the Punjab. After the establishment of the All India Muslim League in 1906, he was asked to enroll himself as a member of the organization. In reply he said: “ I do not mind paying subscription and to become a member provided I am informed in advance of what you write to the government; for the promotion (of my interests) depends on the higher officials” (Tiwana to Wiqar-ul-Mulik, 26 January 1908. Muslim League Papers, vol. 56). To another question in which he was asked to give his opinion on the “Reforms Scheme” circulated by the Government, Tiwana answered that he could not do so because of his connection with the Government. (8 Feb. 1908. Ibid), meaning a servant of the government.

So, there was little or no hope that the aristocrats among the Muslims would contribute for the improvement of the socio-political conditions of their coreligionists. This was left to the middle class Muslims to shoulder the responsibility and they did not hesitate to take steps in this direction. Two names are prominent at the initial stages of this kind of work. These are Mian Muhamamd Shafi (1869-1932) and Fazl-i-Husain (1877-1936).

Following the formation of the social and Political Organization by Wiqar-ul-Mulk in the United Provinces in 1902 these two men in the Punjab took steps to found a Muslims political organization on similar lines. It was not however before 1905 that the two men began to take practical steps in this connection. Before the year ended Fazl-i-Husain completed all the formalities, and found the organization which he named “Muslim League”. Shafi however did not seem to agree with Fazl-i-Hussain and he came out with the idea of the “National Muhammedan Union”. It was most ironic that no sooner the two men had conceived the idea of forming a political organization they began to disagree as to its name though the objective was the same. The difference of opinion for which the foundation was laid in 1905 had adverse effect on Punjab Muslims, politics (details are to found in Report. (Urdu) Punjab Provincial Muslim League, 1907).

The seed of differences sown in 1905 continued to plague the Punjab political activities for many decades. The immediate impact of this was to be seen in 1906 when delegates from all over India assembled at Dhaka in December 1906 to form an all India political organization with the object to protect Muslim political and other rights in the country. The two men appeared there with their own band of supporters. Each one claiming to be the representative of the Muslims of the Punjab. The dispute continued even thereafter in 1907 and 1908 on the occasion of Karachi and Aligarh sessions of the All India Muslim League.

Taking note of this sorry situation a certain Chiraghuddin ‘Roshan’ in two articles contributed and published in Municipal Gazette Sadai Hind, on 12 and 19 December 1907, appealed to Wiqar-ul-Mulk to take note of the sorry situation and to use, his influence to bring an end of the dispute (Muslim League Papers, vol. 2). It was all the more necessary because Fazl-i-Husain insisted that his “Muslim League” founded in 1905 was the genuine one and Shafi who had now started the Punjab Provincial Muslim League as an affiliate of the All India Muslim League claimed to be the true representative of the Muslims of the province. A certain Ghulam Sarwar Khan also wrote to the Wiqar-ul-Mulk on the same subject 23 Feb 1908, Muslim League Papers, vol. 56).

Now that the India Muslim-League had been founded the discord among the Punjab Muslim leaders had an adverse effect on the former. While taking notice of the harmful effects on the All India Mulim League, the leaders made strenuous effort to bring about an understanding between Shafi and Fazl-i-Hussain. This effort was seriously made in March 1908 when annual session of the Muslim League was arranged in Aligarh. They were successful to some extent when Shafi agreed to add a few of the names presented by Fazl-i-Hussain to the list of office bearers of his branch of the Muslim League and Fazl-i-Husain conceded the demand of merge his “Muslim League” into the Punjab provincial Muslim League of which Shafi was secretary.

On return from Aligarh Shafi reminded Fazl-i-Husain of the agreements reachers about there. He wrote:

With reference to the understanding which was finally came (sic) to between you and myself at Aligarh on the occasion of the meeting of the All India Muslim League in the presence of the Nawab Wiqar-ul-Mulk and other prominent members of the League regarding the incorporation of your League into our Provincial League I write to ask you whether as promised by you on the aforesaid occasion you have explained the terms of that understanding to the members of your body and whether you have obtained their consent thereto (Shafi to Fazl-i-Husain, 25 March, 1908).

To the Fazl-i-Husain’s answer was brief but noncommittal. He said:

Regarding the --- Provincial League --- I explained the terms of the understanding to several members individually and then on their suggestion called a meeting. There was lengthy discussion but noting was definitely settled (Fazl-i-Husain to Shafi, 26 March 1908, Muslim League Papers, vol. 56).

The two men could never agree among themselves as the future development showed and Fazl-i-Husain went his way as did Shafi. But an immediate setback to Shafi of this discord was to be seen on the occasion of an election to the Punjab University Council to which Shafi was a candidate. His revival group of Fazl-i-Husain though having few votes, did not vote for him and helped a non-Muslim candidate instead. Lamenting over the situation Musa Khan regretted to Shafi over these state of affairs in the Punjab (Musa Khan to Shafi, 20 December, 1909 Muslim League Papers, vol. 22).

Muhammad Shafi was successful keeping Fazl-i-Husain away from the mainstream of the Muslim politics. As result Fazl-i-Hussain began to look at other avenues. All India National Congress was to be his answer with which he remained associated for some years. His turn to find a niche in the All India Muslim League however appeared in 1915 when Shafi due to difference of opinion with regard to Muslim participation in politics while the Great War (1914-1918) was going on in the Europe. As England was also involved in the War, Shafi was of the opinion that the All India Muslim League should cease its activities till the War was over. No political organization worth the name can survive by suspending its activities on any ground unless of course ban had been imposed by the government on such activities. Most members within the All India Muslim League were opposed to Shafi’s opinion. Syed Wazir Hasan (1874-1947), who was Secretary of the Central Body managed to outvote Shafi from the Muslim League and elected Fazl-i-Husain from the Punjab. Thus, for a few years until Shafi stayed out of the Organization Fazl-i-Husain remained within the All India Muslim League. But his presence does not appear to have any deep impression, not to speak of long lasting, on the policies of the All India Muslim League. He seemed to have lost, or did not seem to have any interest in the all India level politics. After a few years of absence from the All India Muslim League Shafi staged a come back and played an effective role as a leader of the Punjab and also as an all India Muslim Leader.

Fazl-i-Husain’s ouster from the Muslim League both at Central and Provincial levels, had much adverse effect on Muslim politics in the Punjab so much so that the organization could never develop strong roots in the province. By 1919 when the Government enacted a new Act in the country, regional or provincial politics had gained ground over-national grade politics. Fazl-i-Husain who once dreamed of being the national leader of Muslim India concentrated now more heavily on local politics and preferred to be a regional leader over being the national leader. The All-India Muslim League leadership, on occasions, it must be added, did try to draw Fazl-i-Hussain towards it but failed to win him over.

Between 1916 and 1922 Fazl-i-Hussain’s presence in the All India Muslim League did not prove of any consequence. One reason for this was that he still maintained his relationship with the Congress and worked for it. But even the Congress leadership seems to have frustrating effect on him. This is evident from his communication to Syed Zahur Ahmad (d. 1942), Secretary of the All India Muslim League.

“I am not under-taking the next Congress work” wrote Fazl-i-Husain in 1923 “because Congress seems to be cutting itself adrift and dispensing with the services of all the old workers” (Fazl-i-Husain to Zahur Ahmad, 16 Sept, Muslim League Papers, vol. 130). Already Fazl-i-Husain had been working to establish a Punjab based political organization which would be composed of Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs.

Ashiq Hussain Batalvi (d. 1989) In his Iqbal Kay Akhri Do Saal, has provided details with regard to the circumstances leading to the birth of his organization, called the Unionist Party along with its aims and objects so we need not go into those details here. But what it entailed was a setback to the All India Muslim Politics. Besides it sowed seeds of conflict of a serious nature between the Central Muslim political body, the All India Muslim League and the Unionist Party.

While Fazl-i-Husain turned to local or regional politics Shafi remained staunchly centralist and national in his political approach to India’s multi-faced problems of constitutional and political nature. Both Shafi and Fazl-i-Husain seems to have been victim of their personal considerations which are the hallmark of Punjab politics in which tribe, Biradri and personal likes and dislikes play an important and significant role in maintaining relationship between any two individuals. However, it should be conceded that Shafi maintained a consistent policy and remained loyal and true to Muslim interest of both Punjab and Indian Muslim while Fazl-i-Husain turned his back from the Indian Muslims to save the Punjab. This appears to be the result of his earlier failure to make a sound place within the All India Muslim League. He also seems to be a victim of his frustration which he had due to his failure to win a position in the Indian Civil Service the examination of which he had failed to pass despite making two attempts.

It has been generally argued that with his concentration on the Punjab Fazl-i-Husain was able to provide much relief to Muslims. But this seems to be an exaggerated view. As late as April 1947, Iftikhar Husair Khan Mamdot (1906-1969) complained that Muslims have not been benefited under the Unionist Party, founded by Fazl-i-Husain and now being nurtured by his successor Khizr Hayat Khan (1900). Mamdot charged the unionist government of the Punjab that the “Muslim majority of the Punjab had been dominated and ruled over by the minorities “(Dawn, Delhi, 15 Apr. 1997 reproduced in Dawn, Karachi, 15 Apr. 1997) Mamdot further argued in the light of facts and figure how badly Muslim remained underrepresented in the various departments of the government of the province.

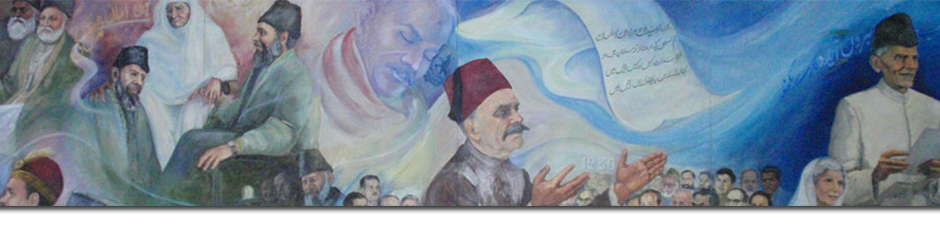

The conflict of these two Muslim leaders of the Punjab, which took its roots early in the twentieth century cost Muslim heavily. As a consequence the All Muslim League was never able to have a firm foot in the province. It seems the seed of discord sown has remained and not weakened even in our own days. I would like to conclude this brief study on the versus of Allama Iqbal (1877-1938) the great sage and philosopher of Muslims: this reflect his assessment of Muslim Punjab, which seems still valid.